Siu Nim Tau (Little Idea)

Siu Nim Tau is one of the three form-sets of the Wing Chun martial art. It is the foundational form-set to begin with. Its emphasis is on maintaining a motionless state of the body, only with the two arms actively shaping into different form structures; yet the power so attained is enormously destructive in offence and strongly sustaining in defence. A closer look reveals that every form taps maximally on the principles of mechanics – endowing Siu Nim Tau with the essence of being the most important basic form-set.

Practising Siu Nim Tau entails undivided attention; casual or perfunctory attitude is detrimental. When the techniques embodied in every form have been precisely acquired, the usage of every structure fully explored and familiarised (which is further concerted with the skills delivered by the other two form-sets, Chum Kiu and Biu Jee), one can then generate as much power as one’s body potentially possesses – power will not be consumed in vain but is always at one’s disposal.

Above all, practising Siu Nim Tau can foster a kind of intangible power. When in operation, such power can hardly be detected in appearance nor exhibited as the contraction of muscles. Instead, no fatigue will be felt even when encountering an impacting force. In fact, massive power is actually being sent out. Such intangible power is termed Nim Lik.

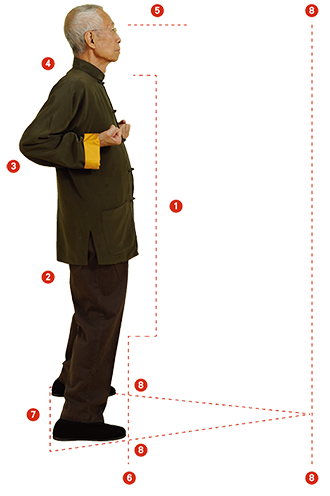

The Stance

- Keep the body as one by aligning the spine and the thighs in a straight line (TN: view from the side).

- Slightly pull up the buttocks inwards (also described as holding the anus).

- The level of the elbows is slightly lower than the fists’ level.

- Sink the elbows and drop the shoulders.

- Keep the eyes on horizontal level.

- Bend the knees slightly until they are vertically above the toes; the knee joints must be relaxed.

- The feet should be placed shoulder-wide apart as though on a straight line.

- The knees and the toes point and focus onto the attack point, that is, the vertical point where the kicks from both legs can reach.

In addition, high concentration must be maintained so that Qi can fill up the whole body. Such posture can transfer external pressure down to the legs, sharing the burden borne by the arms.

Generation of Nim Lik (Mind Force)

The key to practising Siu Lim Tau is to initiate every movement of a form by using Idea, which is only possible with dedicated focus and concentration. In every movement it harnesses, Idea performs a critical role in converging all the bodily energy and strength onto the attack point, as different from brute force generated by contracting muscles. The above description appears not to be immediately comprehensible to beginners. Nevertheless such power does exist. To accord it with a precise name is itself not straightforward too – the concept, Nim Lik, is adopted as a proximate name. If a learner can successfully acquire Nim Lik, he will find it easy and effortless in delivering enormous power contained within all the Wing Chun forms.

Nim Lik is acquired through practising the Siu Lim Tau Form-set. The stance in Siu Lim Tau already exhibits a posture of the entire body being filled up with power. Or, to put it alternatively, filled up with Qi. It is agreeable to those who know Qi Gong (TN: a Chinese traditional skill of cultivating, roughly speaking, internal energy, which is referred as Qi) that the magnitude of Nim Lik is dependent on the amount of and the concentration in training. Unceasing training unfolds its existence; persistent practice further harnesses its power.

When practising the full form-set of Siu Lim Tau, the flow of Idea should remain uninterrupted, always be kept continuous. The purpose of Siu Lim Tau – to discover the existence of Nim Lik – can then become possible to attain.

Once successfully acquired, Nim Lik acts as a kind of endless energy that can never be used up.

Chi Sau (Sticking Hands)

Two points set apart, straight line the shortest mark,

Come hi, go bye, hand freed fists fly.

A pithy yet decent poetic rhyme concisely reveals the way of attaining swift response, solid defence and fierce attack through Chi Sau practice.

The ways of applying Chi Sau techniques are numerous as well as profound. Descriptions such as “mercury poured over every corner” and “proof even against splashed water” (TN: metaphors, in Chinese, praising the comprehensive coverage of offence, the former, and defence, the latter) are only vivid depictions in martial arts novels; they cannot benefit one’s learning in any way.

The applications of Chi Sau are diverse and many. They cannot be satisfactorily depicted even by serial drawings. A better way is to list and explain the various applications one by one, followed by an elaboration on the relationships among them. It is hoped that the learner can then glimpse the techniques involved in each application, so that subsequently he will thoroughly understand the usage of Chi Sau.

The applications of Chi Sau are numerous as well as profound. The basic requirements for its proper practice can be grouped by using the following descriptions:

- Practise for the sensitivity to receiving force, and for swift response.

- Train oneself to acquire the operation of arc-bridge mechanics as manifested in using Lay-flat, Wing-arc and Tame-force Hand-forms to sustain impacts from the opponent.

- Apply rotational force along an arc or circular shape to destabilise the opponent’s balance.

- Detect the opponent’s openings (when in contact) for attack.

- Create settings advantageous to oneself.

- Orchestrate the following four different powers:

- Power from bodily strength;

- Sustaining power from the structure of forms;

- Nim Lik; and

- Power from body weight in motion.

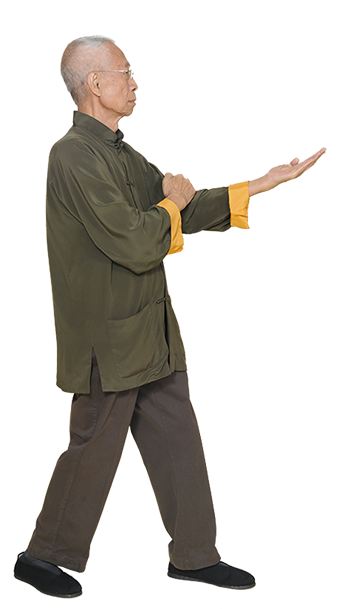

Chum Kiu (Seeking the Bridge)

Chum Kiu is the second fundamental form-set of the Wing Chun martial art. It denotes the exploration of diverse skills in treating the opponent’s hand-bridges when in contact. It trains the learner to acquire the ways of mobilising the body weight as a propelling force which is further orchestrated with the form structures of Siu Lim Tau to result in all sorts of dynamics in Wing Chun.

Making Wing Chun dynamic is easier said than done. It entails extraordinary persistence in practice, disallowing aggressive attitudes and the idea of offence. There are no speedy moves in the entire Chum Kiu Form-set, so that the form structure established through Siu Lim Tau can be accorded with the propelling power of the body weight and the waist- linked stance. Such accordance, once attained, opens access to the wonderful and amazing techniques of force application that, yet, still tightly obeys the principles of mechanics. When skillfully applied, both Propelling Power and Steering Power can be thoroughly manifested – one can appreciate the wisdom and might of the creator of this martial art.

The conception of force application in Chum Kiu is analysed below based on my personal experience:

- Mechanics of Chum Kiu;

- Offence and Defence in Chum Kiu; and

- Force Application Techniques in Combat.

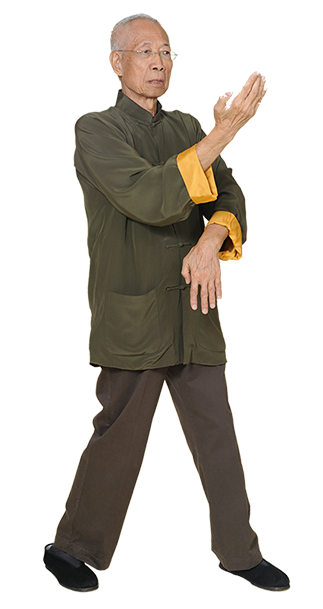

Biu Jee (Darting Fingers)

Biu Jee is the third form-set in the Wing Chun martial art. Traditionally Biu Jee has been regarded as prohibited to outsiders. Grandmaster Ip Man had also mentioned that it would not be taught to others not of his lineage. This might be due to some old thinking that heritage is proprietary, or due to the fact that those who have not built a solid foundation in Wing Chun are not ready to receive Biu Jee training. I believe the latter explanation to be more reasonable.

In fact, the conception of Biu Jee is completely different to that of Siu Lim Tau and Chum Kiu. Its name already hints at the idea of offence: the power from the entire body can be mobilised up to the palm and fingers, enabling massive destruction – it is a very practical set of techniques in combat.

Under the influence of the tradition “prohibited to outsiders” and the fantasy of Biu Jee’s high offence techniques, learners are prone to mistakenly equate learning Biu Jee to being gurus in Wing Chun. They yearn for accelerated access to its training, or start on their own by imitation, diminishing into mere copy-cats. Undoubtedly Biu Jee is practically geared to combat. However, operating Biu Jee is completely based on the achievements in Siu Lim Tau and Chum Kiu training. For ideal and serious Wing Chun training, Biu Jee should not be taught without considering a learner’s readiness – this is, rather, the correct attitude to heightening the learner’s final attainment.

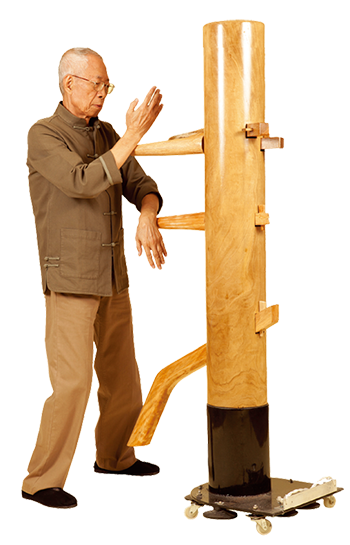

Mook Jong (Wooden Dummy)

The Wooden Dummy is an auxiliary appliance facilitating the training of Wing Chun. The entire form-set of the Wooden Dummy comprises of diverse combinations of the forms of Siu Lim Tau, Chum Kiu and Biu Jee (EN: refer to Volume 1, Parts 1, 3, 4). The Wooden Dummy serves as a target object onto which different applications of forms are practised.

For this reason, the Wooden Dummy form-set is not self-contained. Rather, it is an aggregate of various forms derived from the forms of the foundational form-sets, slightly modified to become practical moves for use in imagined combat situations. This signifies the transition from empty-handed practice to application for combat.

There are 10 sections in the Wooden Dummy form-set. Each section groups, by and large, 10 moves of similar purposes. In addition, there are eight moves of kicking. All this sums up to 108 moves of the form-set.

According to the oral narrations by Grandmaster Ip, the second section (could be regarded as the secondary 10 moves) was originally placed at the ninth section. Grandmaster Ip opined that the moves in this section were the same as those in the first section and thus rearranged the order to make it the second. Whether the original sections were distanced deliberately due to some undiscovered secrets is unsure, something that I have not delved into.

The count of 10 moves in each section of the Wooden Dummy form-set is not a precise measure. For some sections, there are as many as 15 moves. No wonder there are alleged versions of different counting, respectively suggesting 116 and 132 total moves in the form-set.

Meanwhile, Grandmaster Ip often treated the Wooden Dummy as the practice partner for experimenting new moves he had conceived. I had been influenced by his attitude and practised with the Dummy in the same way. However, the newly conceived moves had not been merged into the Wooden Dummy form-set, so that its original composition could be preserved.

As such, I suggest that when practising with the Wooden Dummy, apart from familiarising with the traditional forms, the learner can also try out new moves that are self-conceived, practising them as ad hoc forms. This on one hand can fulfill one’s satisfaction, and on the other hand enrich one’s training mood.

Practising the Wooden Dummy forms brings about various benefits. The immediate benefit (on the external) is to hammer out all the proper hand-forms, leg-forms and the waist-driven stance. This, in contrast, could be hardly attained in Chi Sau practice in which only little time would be allowed for applying the forms correctly – one would only feel incompetent in manoeuvring.

For benefits to the internal, it requires dedicated exposition to uncover the essence of the Wooden Dummy form-set through concise analysis, making it more available to and comprehensible by learners in the future.

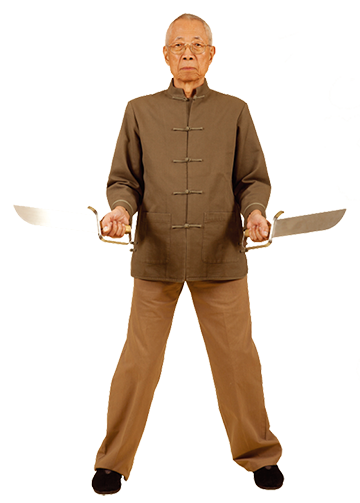

Butterfly Swords

Wing Chun’s Butterfly Swords Form-set can be regarded as fully derived from the diverse form combinations of the three empty-handed form-sets of Wing Chun. Its application thus also appears to be similar to the latter ones. Nevertheless, the stepping forms of Butterfly Swords are uniquely different: they aim at delivering the power from the entire body onto the knives themselves, so as to energise every move of the knives with the heavy and solid body momentum. The details of applying body momentum onto the knives are similar to those of hand-forms. They will not be further elaborated here (EN: for full explanation, refer to Volume 1, Parts 1, 3, 4).

Butterfly Swords emphasises the use of wrist power. In every move, the wrist power is smartly tapped to manifest the skills in deploying forces, making every move of the knives heavy and solid, smooth and with ease, as well as potent and domineering.

To facilitate the actual practice, there are two basic moves to get hold of as a preparatory step: one is Triangular Stance; the other is Double Circling Knives. Once familiarised, the stepping method and the circling of knives will greatly enhance the grasp of power generation in actual training.

Butterfly Swords Form-set involves two knives, one held by each hand and operated simultaneously. The knives are relatively short in length. In combat usually one knife attacks while the other defends at the same time. When being pressed by a heavy weapon of the opponent, so heavy that it could not be sustained by just one knife, double knives should then be jointly used in defence, aiming for an immediate fight-back.

Butterfly Swords is classified as a kind of short (in length) weapons, the characteristics of which are vividly reflected by a Chinese saying on weapons: one inch short in length, one inch close to risk. As such, short weapons can only win by manoeuvring risks for knockout opportunities, adopting the strategy of combating fast for an immediate victory.

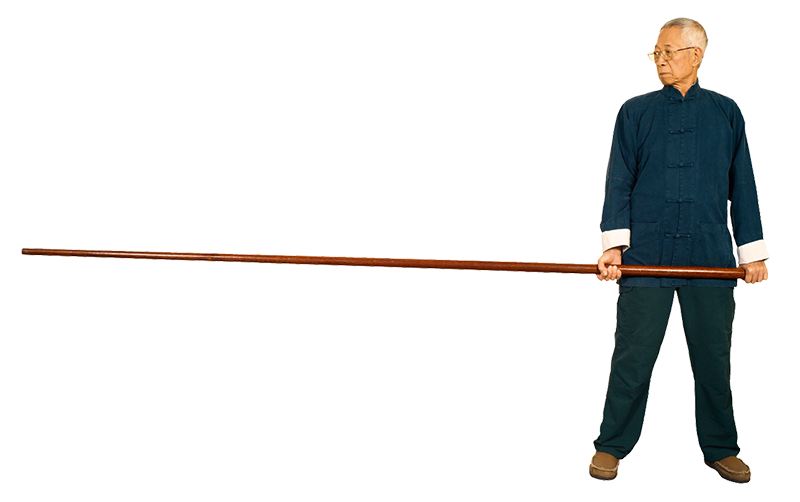

Six-Point-and-A-Half Pole

Wing Chun’s Six-Point-and-A-Half Pole, according to the narration of Grandmaster Ip Man, was not created by Great- grandmaster Wu Mei (TN: Ng Mui in Cantonese). Instead, it was acquired by exchanging the Siu Lim Tau Form-set with Zen Master Zhi Shan (TN: Chi Shin in Cantonese) by Liang Er Di (TN: Leung Yi Tai in Cantonese) and Wang Hua Bao (TN: Wong Wah Po in Cantonese). This happened on the “red boat” (an actual boat serving as the mobile abode of a Chinese opera troupe) where they came across each other. It was told in this way and I have not investigated whether the story is true.

Six-Point-and-A-Half Pole is simple and clean. As its name literally tells, there are just six and a half moves in the entire form-set. Like other Wing Chun empty-handed form-sets, the Pole Form-set does not display complex movements or a taste of grandeur. Lacking the visual attraction that usually causes learners’ concentration to gravitate towards practice, no wonder the Pole Form-set has failed to become popular.

Nevertheless, when accorded with Nim Lik and used in the Wing Chun way, every move of the Pole Form-set will be able to generate power that shocks everyone. Such massive destructive power, embedded within the simple and clean outlook of its moves, is exactly the uniqueness of the Pole Form-set.

Prior to the actual practice of the Pole, one must take on familiarising with several preparatory moves, the purpose of which is to ensure better stability of one’s structure during the actual practice, preventing the body and the stance from loosening caused by the uncontrolled flapping force of the moving pole. Moreover, it would be easier to grasp the skills by taking on the moves through continuously practising them one by one. To achieve perfection, however, the Nim Lik in Siu Lim Tau, the pivoting of the waist-driven stance in Chum Kiu, the Sending-power-to-fingertips in Biu Jee, and the mechanics of cumulating power in Wooden Dummy are all inevitable. For this reason, these several preparatory moves should not be overlooked. Rather, one should seriously train on them hard so that results can be attained more easily in forthcoming practice.

Length of the Pole

As told by Grandmaster Ip Man, the pole he used for training in the old times bore these dimensions: length, nine Chinese feet; diameter of head, 1.2 Chinese inches; diameter of tail, 0.9 Chinese inch. (1 Chinese foot = 10 Chinese inches; 1 foot = about 8 Chinese inches.) Using longer poles for training can strengthen one’s bodily power. It is also more ensuring for the future that one can handle poles of various (shorter) lengths. Otherwise, if using shorter poles for training, one will find it hard to harness longer poles, just being clumsy and not able to achieve the desired effect. The poles being used in Hong Kong are mostly nine feet (not Chinese feet) in length, giving an easier task in training to learners nowadays than before.